Jack Smith paints portraits.

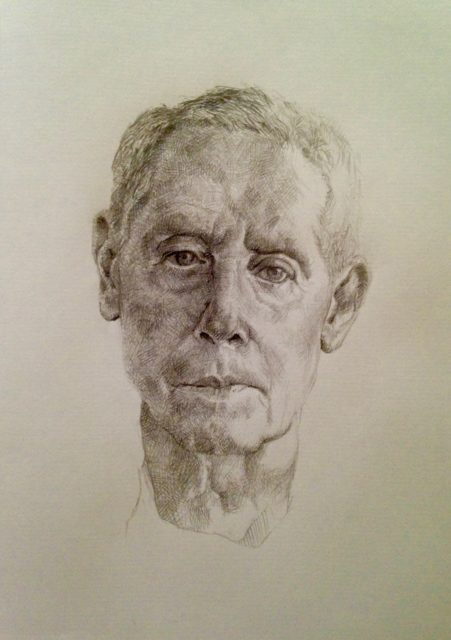

Not just any portraits. Jack’s paintings are so good and he is so incredibly talented, it’s difficult to know where and how to begin describing his work. Masterful and modern, yet steeped in tradition, Jack makes art that transcends trends and fashion; these works on paper, canvas and metal will surely stand the test of time.

I’ve known Jack and his lovely wife Kim for decades – our kids grew up at the same time, here in Taos – part of an extended tribe that included the Hopper- Concha clans, the McCormicks and of course, the late Bob Watkins, who was the glue binding us all together.

I’ve been meaning to include Jack on the blog since its inception, but for one reason or another, our timing was off.

Better late than never, I shot him a few questions via email a week or two ago and I’m delighted to introduce him and his work to you now.

Q:. You are from Michigan (where you grew up knowing Michael McCormick, one of taostyle’s Sponsors), can you please tell my readers how you wound up in Taos?

JS: In the early seventies I drove through Taos on my way to Tucson to visit friends with the vague idea that I might relocate. I drove in by way of Taos Canyon and up Kit Carson Road. The impact was stunning and wonderfully foreign. I’d attended college in Mexico and immediately felt at home with the adobe architecture, the exoticness and vowed to return. Two years later my father, declining from a protracted illness was dying and I was having a difficult time with it so a writer friend suggested we fly to Los Angeles and drive to San Francisco with a brief stop in Taos on the way. We had both been introduced to Zen Buddhism and my friend wanted me to meet a priest who was also involved with the film industry and was living at “The Big House”, the Mable Dodge house, helping Dennis Hopper edit the Last Movie. It had rained during the night of my arrival and as I awoke I was overwhelmed with the smell of wet sage and the low clouds around the mountain. I immediately went to a phone booth, called my wife Kim and suggested that we move. It didn’t take much convincing and forty years later we still keep a home here.

Q:Your work is really special – very classical in that you are a figurative painter at a time when figurative painting and portraiture are not in “fashion”, but extremely contemporary at the same time, especially in your choice of subject matter -has that adherence to classical form, composition and media hindered you in any way during an era devoted to (often dubious) art?

JS::Austrian film maker Michael Haneke said; “Classicism becomes avant-garde when everyone else is doing their upmost to develop new stylistic forms.”Though I am tangentially aware of what other artist are doing I don’t pay much attention to current trends. There’s just too much out there and little of it touches me in ways that I react favorably to. As with much else, cleverness is interesting briefly but I remain unclear about its longevity beyond a year or two of fashion.Whether or not this approach has hindered or helped my career, I’ll leave that to others to consider. I just continue to make what gets in front of me and try my best to follow my instincts. I was classically trained when I was very young by a family friend, a renaissance man, architect, sculptor and painter. My father who was always very supportive of my inclinations toward art paid for lessons with him. While my friends were playing baseball, I was spending hours in his studio in awe of his limitless abilities, depth of knowledge and largess of generosity to allow a ten year old work with him. He taught me the fundamentals of materials and techniques and art history. Because I grew up on a farm in a rural area in the lake country of western Michigan I didn’t have much exposure to what was going on in the art world at large so I was imprinted early on to adhere to classical forms. I attend Interlochen Arts Academy when I was fifteen and was thrown in with some of the most talented young artists of all disciplines from around the world. The experience cracked me open in many important ways. Imagine, one day sitting across the lunch table with Van Cliburn and the next with Werner von Braun. Heady stuff for a fifteen year old farm kid. That’s alluvial gold for any young creative mind. Subsequently I went off to college and studied current movements but the die had been cast and though my work was in some ways informed by those movements I never veered too far away from classical forms.

Q: You paint on metal (not glass), and other surfaces besides canvas and linen – do tell how and why that came to be

JS: I had a studio mate years ago who had been head of the department of education at the Whitney, he was also teaching art history at Princeton and had an epiphany one day that he really didn’t have a hands-on knowledge of what it was he was teaching. He left his positions and wandered around Europe for seven years studying old mediums and grounds. He spent time with real artists, visited galleries with portraits (like the ones in Charles Saatchi‘s), and shared a good deal of information with me and I was inspired to take a serious interest in techniques and mediums of the Dutch schools. After that I more or less locked myself in an attic studio in a Michigan farmhouse for several years to learn how to use the materials. I use “black oil” mediums favored by Rubens, Hals, Vermeer and others which incorporate a bit of alchemy, beeswax, lead salts and various oils. One ground used at that time was copper plate which is a “living” metal and of course they also used linen and wood panel. Copper has many alchemical properties and the whole system gives a depth I don’t seem to get with more opaque tube paints. I also like the romantic notion of keeping alive the trajectory of a tradition. Copper for large paintings has gotten prohibitively expensive and it is also heavy and though I have painted large works on copper I usually go to canvas or linen if working big.

Q:Your work has appeared in Museum and Gallery shows, you have painted the famous and not so famous – looking back how do you see the trajectory of your career in hindsight?

JS: I have been very fortunate and remain grateful that opportunities have presented themselves to allow me to get up in the morning and make things, buy homes, raise a family and travel. I have painted Nobel Laureates, movie stars and rock stars, rich and poor and the disenfranchised. Not everyone gets that opportunity. I’ve been able to meet, spend time and collaborate with some very remarkable people. I get to study the human experience in a very intimate way and have concluded that there are a lot more similarities than differences. And as it turns out from my observations, success and money are not a magic carpet to happiness. I began painting portraits out of necessity to save me from getting a real job when we had a young family. No one was rushing my door to buy my other paintings so I thought to appeal to the vanity of potential clients. I considered it more of a craft then though in time when I began serious research of the genre it became my main focus. Humans are odd creatures and continue to fascinate me and currently have two commissions, one ready for delivery in Miami and another nearing completion for a client in France. I also have two painting series in the works, Portraits of Cuban Poets and another with a working title of Sanctuary Eyes, eye portraits of individuals from various countries who are dealing with the current administration’s unfortunate policies and resultant fear of deportation. I’ve been aided by several immigration organizations here in New Mexico and elsewhere. Jose Gonzales with Las Cumbres here in Taos has been remarkably helpful as well as the New Mexico Faith Coalition. The completion of both of these series is difficult to determine because they involve the lives and schedules of a lot of people. We have a good deal of interest with museum venues for future exhibitions. I’m doing a lot more writing these days and slowly working on a screenplay that has languished for years between other projects as well as several short stories. An advantage of age is that my priorities have changed. I’m not as hungry as I used to be and time has become more precious so I choose my projects more carefully. Jim Harrison wrote me years ago about the trajectory of a career in the arts summing it up with; “by the time recognition finally happens the only things that matter are family, good food and better wine”. I concur.

Q:Can you tell us a bit about your process – about the seeds of inspiration that inform your work?

JS: I seldom take notes and never preliminary sketches, though I often do so after the fact if a certain passage in the painting troubles me. If an idea is worthy of committing to paint, it will resurface at the right time. We have a million thoughts a day, which ones make through the gauntlet of process to being fully realized as a painting is a bit of a crap shoot for me. We have so many tools at our disposal now. How one gathers information, sketches, camera, interviews or video and computer programs are just devices to get the job done. The most important element in portraiture is spending enough time with the subject to understand who they are, hear their voice, their personal narrative, how they navigate the relative world. I have many stories about first impressions being totally wrong so I’ve learned that the longer I’m able to spend time with at subject the more informed the portrait is. What separates portraiture from other genres of painting is that we invite another being into the process. It’s a collaboration, an inviolable trust and one I take seriously. I’m rather circumspect about choosing subjects and more so as I get older. It takes an odd audacity to enter into portraiture as we are fundamentally stirring the waters of the perception of self and other and the subject’s vanity. The Russian cultural critic Mikhail Bakhtin coined a phrase; “an excess of seeing”. What he meant was that you can see all of me but no matter how many mirrors I have, I will never be able see me as fully as others can. We have frontal vision so our personal mythology about who we are in relationship to the world around us and those observing us is tilted inward. Therefore we have and internal dialogue that weaves a narrative. True that it is based on experiences but filtered through our woven story of what we imagine ourselves to be. It’s a very curious and perhaps unsettling thing to think about. But, it is what continues to fascinate and inspire me. I owe my work habits to farmers and writers, my two earliest influences. Both have admirable work ethics. We have a tendency to lionize and guild artists in an odd way. We live in a celebrity culture where often the person making the work is promoting themselves at three clicks above their competency level. We are first of all, or should be workers. I admire a well made chair over much of what I see in the art world. We are cultural, societal voyeurs and what we do is essentially detective work then documenting and making a subsequent artifact from the data we’ve gathered.

Q:You generally paint quite small pieces but I’ve seen a couple of very large canvases also – what’s your preference?

JS:I don’t really have a preference but rather let the subject matter determine the size. My dialogue with a painting and that of the viewer is predicated on size. For example, if it is an intimate subject I tend toward small grounds to draw the viewer into a closer, more nuanced dialogue with the work, to require them to have personal experience with the painting. It’s about proximity. Larger paintings require one to stand back and that gives the viewer it an entirely different experience. Painting larger work is also more physical.

Q: These days you and Kim spend quite a bit of time in warmer climes – how often do you return to Taos and how long do you stay?

We have been spending our winters in Key West and Mexico and as I mentioned earlier I’ve just recently returned from Africa and soon heading to Costa Rica. Neither Kim nor I care to spend time in cold climates but there’s more to the equation, we both like to travel and winter is a good time to do that. I came by the need to travel quite honestly through my parents. My mother jokingly called it our “gypsy” blood which of course is not the case. I feel most at home in a foreign market where I am completely anonymous, no past, no future, thoroughly immersed, in the present moment. It reboots the creative machine. Lately we have been spending May thru November in Taos to enjoy, spring summer and fall. There’s not a place in my experience quite like it.

Jack Smith is represented by the Paul Mähder Gallery in Healdsberg, CA.,and Daniel Morris / Historical Design in New York, NY.

All images of Jack Smith’s portraits, thanks to Jack.

From top to bottom: Portraits of Kristine McCallister, Jana Hanka and Jose Kozer graphite on buff paper. Portraits of Niccolo Ammaniti, Cedel Davis (featured), and Ara Winter, oil on copper plate.

Jack Smith is one of the finest artists in the world

Thanks M2!

I love Jack Smith’s work! He’s so talented, and a fierce and funny guy, too.

Thank you Barbara for the good words…

Thank you both for commenting. When Jack gets back to town, I’ll do a studio visit as well.

I look forward to a studio visit Lynne….

So do I!